Seasons Greetings all,

Thank you for all your support in 2023.

We have some amazing new series coming in 2024.

We have a perfect sponsor for the Corporate Explorer in the Field series. This is based on the book of the same name and then will feature corporate Innovators. We are grateful to our sponsor Wazoku.

We have another series based on all the work of Rita McGrath if you want to read along, we will cover all her books: The Entrepreneurial Mindset, Market Busters, The End of Competitive Advantage and Seeing Around Corners. There are strong rumours Rita has another book in the works also.

We are seeking a sponsor for our “Innovation Show X” series. This is where we bring two guests together who have never collaborated before and record. live session. It includes Charles Conn X Paul Polman, Paul Nunes X Ian Morrison, Robert Sapolsky X Robin Dunbar and more.

Other guests include Michael Beer, Howard Gardner, Sally Sussman, Wendy Smith, Paul Daugherty, Teresa Amabile, and Ellen Langer.

We have 2 episodes to drop before 2024, one on 3 bio hack devices I am using in 2024 and the other is a longevity exercise regime I have been using for an entire year now, beautifully called “Built From Broken”, both are a little “off piste” from what we normally cover.

Happy New Year,

Aidan

“Nothing retains its original form, but Nature, the goddess of all renewal, keeps altering one shape into another. Nothing at all in the world can perish, you have to believe me; things merely vary and change their appearance.”― Ovid, Metamorphoses

In 1969, amidst global uncertainty and the space race, Elliott Berman envisioned a future beyond fossil fuels. Convinced that alternative energy was the key, he targeted solar power. However, at over $100 per watt, it seemed impractical. Undeterred, Berman set the daring goal to bring the cost down to $20 per watt.

In 1973, Berman founded Solar Power Corporation (SPC) to commercialise the breakthrough. Initial attempts to sell the technology to the Japanese electronics conglomerate Sharp fell through, leading SPC to venture into the market independently. Their first success came when Tideland Signal adopted SPC panels to power U.S. Coast Guard navigation buoys. Undeterred by initial rejection, Berman’s team approached Exxon to use their solar cells on oil-production platforms. After Exxon rejected the offer, Berman and his team eventually convinced Exxon to use SPC solar cells. This move led to solar cells becoming the standard power source for oil-production platforms around the world. Berman revolutionized the industry’s power source.

Berman’s story appears to be that of a typical entrepreneur working for years, without remuneration, incurring large debts, and often relying on the kindness of friends and family to continue.

The twist in this tale is that Elliot Berman was not an entrepreneur. He was a corporate intrapreneur who maintained the security of a salary, benefits, and a budget to pay for the many things that early-stage entrepreneurs learn to do without. (Read more about Berman and others in “Driving Innovation From Within” by Kaihan Krippendorff).

While Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Sara Blakely often dominate headlines, the stories of intrapreneurs like Elliot Berman at Exxon, remain in the shadows. Intrapreneurs can make significant contributions within the corporate framework, pushing boundaries and redefining industries without the same spotlight as their entrepreneurial counterparts. If the corporate culture allows them to.

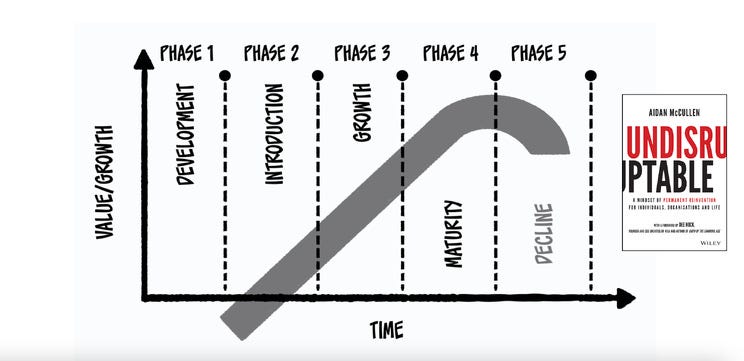

The tragedy of organisations is that every company begins with vision, creativity, agility, hard work and innovation. However, once successful, that flexibility was replaced by rigidity, rules and regulations. Once an organisation reaches a certain point in the lifecycle, leadership sacrifices innovation to order and control to replace creativity. The corporate lifecycle mirrors the S-curve, initially ascending with vision, creativity, and innovation propelling growth.

The Corporate Lifecycle

In the early stages, companies embrace agility, hard work, and a dynamic spirit that fosters breakthroughs. However, as success solidifies, a subtle transformation occurs. The ascent reaches a peak where established rules and regulations take precedence, symbolising a shift from flexibility to rigidity. This transition marks a critical juncture where the organisation, once an agile innovator, now prioritizes order and control. The S-curve graphically encapsulates this journey — the steep rise representing the dynamic inception, the peak signifying the pinnacle of success, and the subsequent descent illustrating the trade-off between innovation and the embrace of structured stability.

So how do we avoid phase five and become undisruptable? The answer lies with phase six and phase seven.

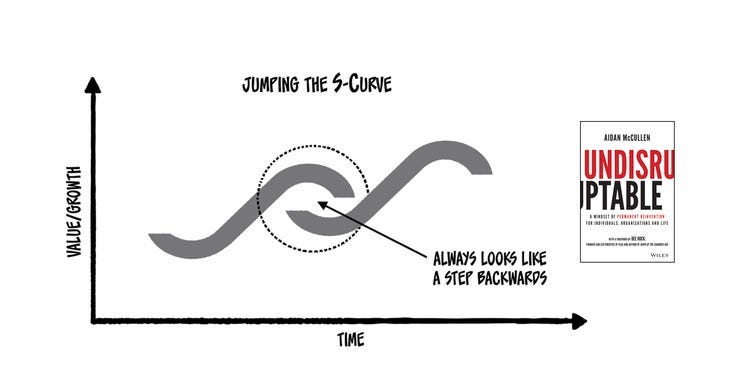

Phase six is “Jumping the S-curve” a term used in business to describe a strategy where an organisation seeks to leap ahead to a new phase of growth or innovation rather than following the traditional linear progression along the S-curve.

Jumping the S-curve involves making a significant leap to a new curve before the current one plateaus. This strategy often requires a disruptive innovation, a radical change in approach, or the introduction of a new product or technology that propels the organisation into a higher level of performance or market position.

Many organisations struggle to make the jump for a host of reasons including mental stagnation, competing business models and corporate rigidity that accompanies the end of the corporate growth cycle.

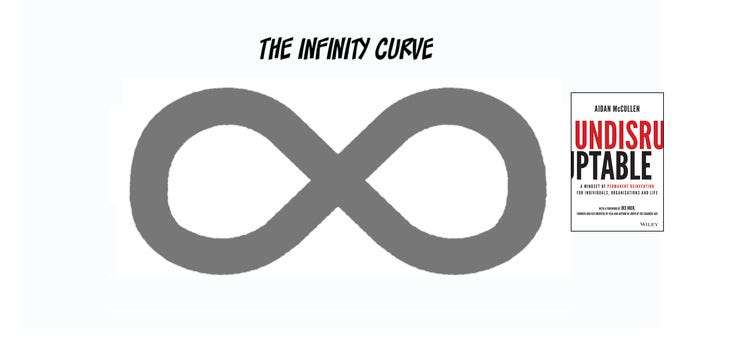

For a long time, I had envisaged an S curve jump as the death of the previous curve. Today, I realise that each curve does not need to die, if correctly managed, the old can fuel the new. The curves are not isolated moments in time, they are arrested moments in a dynamic, plastic and perpetual process. The new curve requires existing resources such as supply chain, funding or marketing, it can depend on the established curve to deliver. The emergent curve reciprocates by delivering new business models, products, services, skillsets and mindsets. They are no longer separate entities, they are one, part of the same process. This radically changes the concept of the S curve from a periodic jump to a permanent cycle, from an occasional transformation to a permanent reinvention. If you consider the S curve doubling back on itself it becomes what I call “The Infinity Curve”.

The Infinity Curve is possible when organisations realise that they have a significant advantage compared to a startup. Many startups aim to be acquired by an incumbent because established organisations have any mix of capabilities, know-how and funding available to bring a budding business model to life.

Startups have access to more capital than ever before and, thanks to software-as-a-service platforms, have narrowed the technology gap between startups and corporations. Even so, established organisations have a significant head start on entrepreneurs in the degree of assets available to them. They have customers, financial resources, manufacturing, customer services, technical expertise, and established trustworthy brands. Making such advantages count is the essence of the Infinity Curve.

Incumbent organisations can enjoy the best of both worlds, exploring their transient advantage today, while exploring budding advantages tomorrow. The way to do this is to follow the infinity curve and leverage the tensions between the old and the new. Corporate intrapreneurs should not have to battle to help the organisation succeed. When organisations nurture playbooks to help these creative individuals succeed, it will help them sustain success in the long run. Every organism is a melting pot of concurrent dying and becoming, an organisation is no different.

Thanks for Reading and Happy New Year

For more on corporate innovation, check out the last episode of the Kaihan Krippendorff collection, “Driving Innovation From Within”.

The Corporate Head Start and The Infinity Curve was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.