“All great truths start as blasphemies.” — George Bernard Shaw

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the seas were treacherous, and scurvy claimed the lives of countless sailors. Among them were brave men sailing with Vasco da Gama in 1497 around the Cape of Good Hope. By the journey’s midway point, almost half of the sailors had died of scurvy.

In 1601, exasperated by the persistent problem, a British captain, James Lancaster, took action. Earlier sea captains had demonstrated the connection between citrus fruits and general health, and Lancaster had the idea to test the impact of citrus on scurvy. While commanding four ships en route to India, he selected one as a test sample. Every sailor on the test ship was given three teaspoons of lemon juice daily; the others received none.

The results were irrefutable: the sailors served lemon juice survived the voyage in good health. Almost half of the sailors on the other ships died.

With such an incontestable outcome, we might expect the British Navy to quickly grab onto this innovation and make daily citrus rations a requirement. However, the British Navy did not adopt the practice until 1795, nearly 200 years after Lancaster’s experiment.

The story is a typical illustration of the prolonged struggle to accept a simple innovation. The delay in implementing such a solution raises questions about the factors contributing to the slow adoption of innovations, even when their efficacy has been demonstrated.

Those of us navigating the tumultuous waters of transformation may perceive that we are grappling with unprecedented challenges. However, the underlying dynamics of these challenges remain remarkably consistent across various industries, organisations, and eras. While the specifics of the competitive environment may vary, the way they affect change agents and organisations follows a familiar pattern.

Several factors continue to emerge time and time again.

Institutional Inertia: Large organisations, especially those with long histories like the Navy, resist change due to established and often entrenched routines, hierarchies, and traditions. Bureaucratic hurdles and resistance to deviating from existing practices play a significant role in resistance to innovation. This inertia can also come from the status of those close to retirement. Why launch a considerable transformation effort when you are close to retirement? “Aprés Moi Le Déluge” (After me, the flood).

Access to or Lack of Communication: While the dissemination of information in the 17th and 18th centuries was limited, there is no excuse in today’s hyper-connected world. Organisation leaders must remain close to their troops and unfiltered sources of information.

(Organisations are so connected today that they can suffer from devastatingly fast adoption, what Paul Nunes calls “catastrophic success.” Paul offers the example of the artisanal apparel start-up American Giant. One favourable mention on Slate.com launched the company into the stratosphere. In a single day, they received 5,000 orders for a hooded sweatshirt — a level of demand the company couldn’t satisfy. “Four days later, we had nothing left,” Bayard Winthrop, the company’s embarrassed founder, told the BBC. “We were down to the sticks in our warehouse.”)

Scepticism and Ignorance: Despite compelling evidence, changemakers encounter scepticism or ignorance among authorities about the efficacy or profitability of an innovation. A lack of understanding or scientific evidence would have contributed to the delayed adoption of citrus fruits, preventing scurvy. Changemakers must work hard to disseminate and ultimately sell the idea. This is the hard part of innovation: the social side.

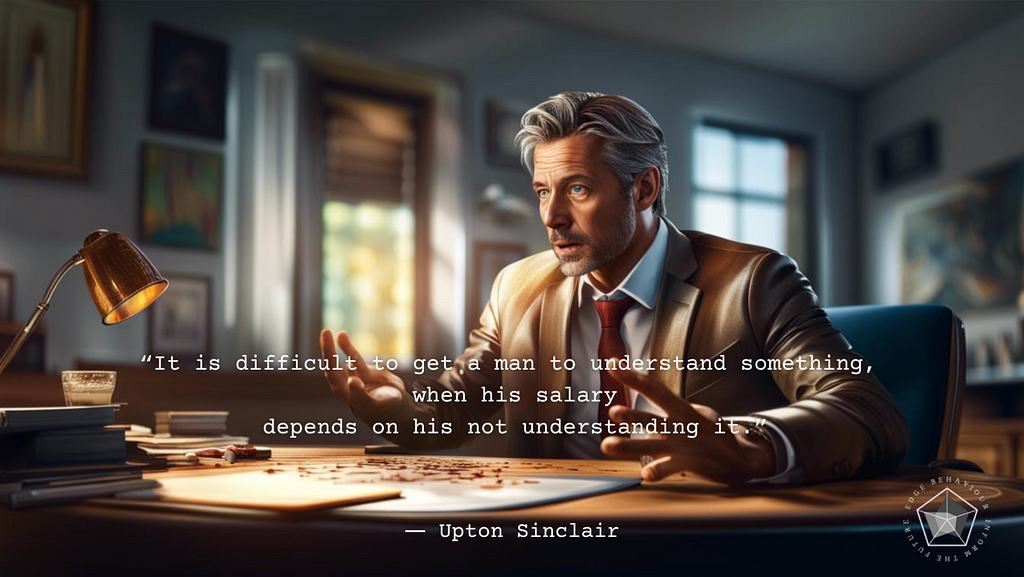

In organisations, however, we must also consider American novelist Upton Sinclair’s timeless words: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” Troy Campbell and Aaron Kay of Duke University presented a research paper called “Solution Aversion: On the Relation between Ideology and Motivated Disbelief.” They propose that people are less likely to believe something’s a problem if they have “an aversion to the solutions associated with it.” This is certainly the case with organisational change initiatives, business model transformation, and disruption.

Cost and Logistics: Implementing a new practice, even as simple as providing lemon juice, involves coordination costs and logistical challenges. Decision-makers are often hesitant to allocate resources or disrupt existing supply chains. This reluctance is amplified when the innovation solves what managers may perceive a minor issue. Any deviation from optimisation is considered a distraction.“In the early stage” (of an organisational lifecycle) -Clayton Christensen observed — “managers are puzzle solvers, not number crunchers.” At a certain stage in an organisational evolution, creativity is stifled, and a focus on cost-cutting and exploitation replaces an openness to exploration.

Hierarchy and Centralised Decision-Making: Decision-making in large organisations, especially military institutions, involves a hierarchical structure. The approval process for adopting new practices is slow, and the decision requires approval from higher-ranking officials. In organisations, a lack of accountability and a low tolerance for risk exacerbates slow decision-making.

In today’s rapidly changing world, we must reconsider the anatomy of decision-making. An organisation is more akin to a murmuration than a hierarchy.

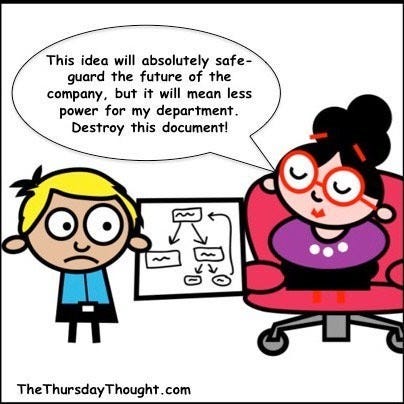

With this week’s Thursday Thought, I intend to remind a change maker that you will undoubtedly encounter resistance to change. The more significant the change, the mightier the resistance. Resistance is rarely centred on a single person or small group of individuals opposed to change. Still, it comes from a Gordian knot of embedded culture, structure, traditions, processes, protocols and people who benefit from the status quo.

When (not if) you meet this resistance and inertia, it is because your organisation is steeped in a particular culture. That culture is what got the organisation to where it is today. That alignment of processes, procedures and people made the organisation successful yesterday. Your innovation threatens that alignment, even when it benefits the organisation’s future. They will gaslight you, ostracize you, and undermine your idea, but please remember this is not a new battle; it is an ancient one.

Thanks for Reading

This article is inspired by my conversations with Kaihan Krippendorff during our series on his work. Part 1 is available now and part 2 is on the way.

When Life Gives You Lemons: Make Excuses? was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.