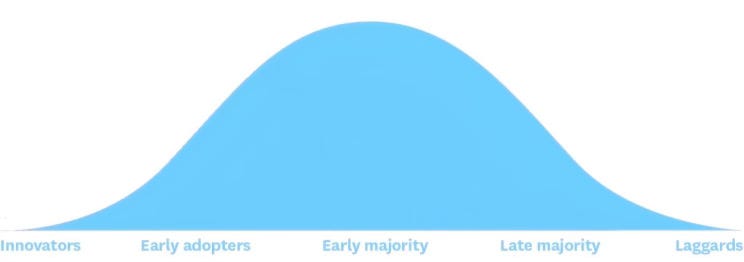

Yogi Berra famously quipped, “Predictions are difficult, especially about the future.”This rings especially true in today’s dynamic business landscape, where innovation cycles are shorter and more unpredictable than ever. The traditional bell curve, popularized by Everett Rogers, which mapped product adoption through distinct segments like innovators and laggards, is no longer enough.

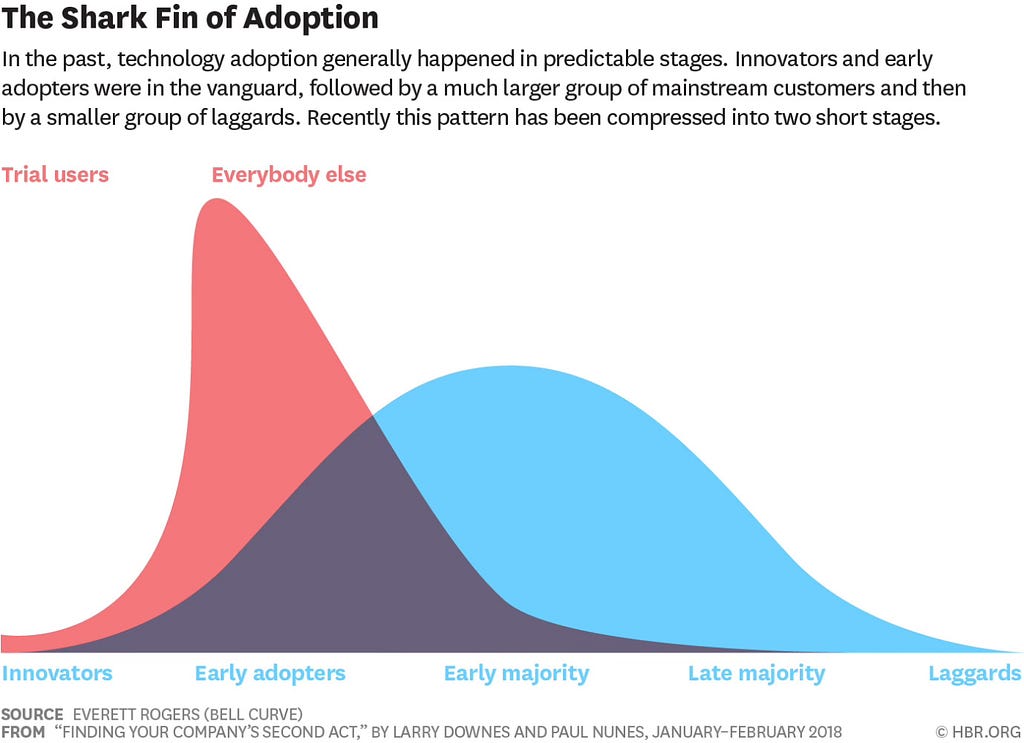

Enter the Shark Fin. Technological advancements and digital dissemination have accelerated the pace of innovation adoption. Consumers can now leapfrog traditional adoption stages, propelling new products to immense popularity seemingly overnight, only to see them fade away just as quickly.

However, a new approach is emerging that offers a lifeline in these turbulent waters: “Proximity”. Proximity refers to a business strategy that focuses on delivering value (products, services, experiences) as close as possible to the moment of customer demand. This involves utilising digital technologies to:

- Shorten the distance between production and consumption.

- Respond to real-time customer needs and preferences.

- Minimise waste and environmental impact by tailoring production to actual demand.

This responsiveness is critical for navigating “The Shark Fin” not just of innovation, but of supply chains and just-in-time manufacturing, allowing businesses to master the initial wave of popularity and then adjust course to meet evolving customer preferences, mitigating the rapid decline often associated with this adoption pattern.

This week’s Thursday Thought dives deeper into the limitations of the bell curve and the rise of the shark fin, explores the American Giant case study of “catastrophic success,” and then showcases how Levi’s “on-demand” innovation exemplifies the power of proximity strategies in the face of this new business reality.

The Bell Curve vs. The Shark Fin: A Tale of Two Adoption Models

Everett Rogers’ “Diffusion of Innovations” theory outlined a progressive market adoption process, with categories ranging from innovators, who embrace new ideas early, to laggards, who are the last to adopt. Marketers have long relied on this bell-shaped curve to understand and adapt to market adoption. While this model can be frustratingly slow for impatient startups, it can also be devastatingly quick for some established businesses.

“There is no business so good it can’t be destroyed by getting inventory wrong.” — Paul Nunes

Paul Nunes, in his book “Big Bang Disruption”, describes this phenomenon as “catastrophic success.” He cites the example of American Giant, an artisanal apparel startup that experienced a meteoric rise after a single glowing review online. The company received a staggering 5,000 orders for a hooded sweatshirt in just one day. This overwhelming demand exposed their lack of preparedness, leaving them with a depleted inventory within four days. Founder Bayard Winthrop described the situation as “we were down to the sticks in our warehouse.” The rapid rise and subsequent decline of American Giant exemplifies the “Shark Fin” adoption curve.

The Shark Fin presents a significant challenge for businesses. Unlike the gradual slopes of Rogers’ bell curve, the Shark Fin features a sharp spike in adoption followed by an equally rapid decline. This rapid rise and subsequent decline can be devastating, not only in terms of lost sales opportunities but also due to the potential for stranded inventory and depreciating assets. As markets for these “Shark Fin” products inevitably decline (what Paul refers to as the Big Crunch), companies face the risk of losing more money than they made during the initial boom.

The following factors highlight the dangers of the Big Crunch:

- Inventory Waste: Overproduction in anticipation of sustained demand can lead to a surplus of unsold products when the market shrinks. This can force companies to resort to fire-sale prices, further eroding profits.

- Idle Infrastructure: The infrastructure built to support rapid growth, such as factories and retail locations, becomes a burden during the Big Crunch. Maintaining these facilities becomes a fixed cost, even when production slows down.

- Unnecessary Marketing: Marketing expenses incurred to maintain brand awareness during the boom period may not be scalable when the market shrinks. The cost to reach a smaller customer base remains relatively constant.

- Legacy Product Support: Obsolete products may require ongoing customer service and warranty support, even when they are no longer profitable to maintain.

- Diseconomies of Scale: While economies of scale lead to cost reductions during periods of growth, the opposite occurs during the Big Crunch. Servicing a smaller customer base with the same infrastructure becomes more expensive per user.

While American Giant’s experience with catastrophic success exemplifies the dangers of the Shark Fin, their story highlights the importance of proximity strategies that allow companies to produce closer to real-time demand, minimising the risk of overproduction. A company that is learning to master proximity strategies to precisely navigate the shark-fin-infested waters is Levis’Store.

Mastering the Wave Machine: Levi’s On-Demand Innovation

“I am not afraid of storms, for I am learning how to sail my ship.” — Louisa May Alcott

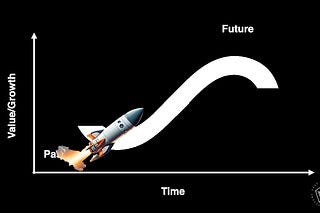

As business systems postpone more and more value-added activities until actual demand, prediction becomes less important. Consider the difference between demand planning for an upcoming season for thousands of finished products against having raw materials and capacity ready to create whatever finished product might be demanded in each unique customer moment. Raw materials can be fashioned into a far wider range of end products, whereas finished products have far less flexibility for end use. Raw materials also tend to have far longer shelf lives. Waste declines — dramatically.

In contrast to the unpredictable and rapid rise (and fall) of American Giant, Levi’s has adopted a more controlled and responsive approach to innovation with its “on-demand” finishing process. This “proximity strategy” epitomises the real-time learning and adaptive systems that are becoming essential in modern business models.

Levi’s Project F.L.X. (future-led execution) and its subsequent development, Future Finish, represent a seismic shift in the denim industry. Traditionally, denim finishing was a manual, labour-intensive, and chemically reliant process. Levi’s innovation introduced a digitally controlled, laser-based system that allows for jeans to be finished to exact customer specifications in mere minutes.

This adaptive approach is akin to turning on and off a wave machine, where Levi’s can meet waves of demand and meet them with precise, controlled production. Unlike American Giant’s experience of riding unpredictable storm waves, Levi’s method leverages technology to respond to consumer demands in real-time. By postponing the final finishing of jeans until customers specify their preferences, Levi’s can mitigate the risks associated with trend fluctuations and overproduction.

A Comparative Analysis

The juxtaposition of American Giant’s catastrophic success and Levi’s on-demand precision highlights two distinct approaches to leveraging technology in the modern market. American Giant’s experience underscores the potential volatility of digital-age consumer behaviour, where a single influential mention can trigger an overwhelming surge in demand. This scenario is much like trying to ride a storm, where the force and direction of the waves are beyond control.

On the other hand, Levi’s approach exemplifies the advantages of integrating real-time learning and adaptive systems. By harnessing digital tools and data-driven insights, Levi’s can remain agile and responsive, ensuring that production aligns closely with consumer preferences. This strategy not only enhances efficiency but also fosters sustainability by reducing waste and overproduction. It’s like having a wave machine at your disposal, allowing you to create and manage waves of demand with precision and control.

In essence, while American Giant’s story is a testament to the power and peril of sudden digital-age success, Levi’s demonstrates a strategic, technology-driven model that embraces flexibility and consumer-centric customisation. Both cases illustrate the transformative impact of technology on market dynamics, yet they also reveal the diverse ways companies can navigate this landscape — either by riding the storm or by mastering the wave machine. Louisa May Alcott’s wisdom reminds us that it is not the storm itself that defines us, but our ability to learn and adapt, to sail our ships through turbulent waters, or to control the waves with precision.

Thanks for Reading

As Robert C. Wolcott and Kaihan Krippendorff tell us in their brand new book, “Proximity”, Proximity strategies differ from traditional approaches by several characteristics we discuss on The Innovation Show. One such example is how proximity strategies enable adaptation as conditions change. Proximity models should be designed to adapt as capabilities evolve. This means anticipating the direction (not the details) of customer needs and which technologies and business models might eventually prevail. Find that episode below.

It includes a bonus live episode of “Proximity In Action” with Dr Ian McCabe on Clare Island, a small island with 150 inhabitants.

https://medium.com/media/c72ad3481d8a904865479755ec0e0bbf/href

Also, find that brilliant series with Pauk Nunes anywhere you get podcasts and here on YouTube.

https://medium.com/media/abb436186a554cc9a08564406c5c05b6/href

Top posts on Substack:

Take the Staircase, Not The Escalator

The Corporate Head Start and The Infinity Curve

Black Walnuts, Broken Windows, Bad Apples

Hire For Neurosignature, Train for Skill: The Brain is Like a Waterbed

From Black Sheep to Black Ops: Unleashing Latent Potential

From Shark Fin Surges to Proximity Precision: How Levi’s Mastered the Wave Machine was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.