“There is nothing more difficult for a truly creative painter than to paint a rose, because before he can do so he has first to forget all the roses that were ever painted.” — Henri Matisse

I love how Matisse’s quote encapsulates the mental traps of expertise and experience. Imagine an artist standing in front of a blank canvas, poised to create something new amidst the mental reverberations of roses past. This symbolises the tension between the pursuit of something new and the weight of convention. Experience can be a dual-edged sword.

Assumptions and beliefs often stem from past successes, gradually shaping “the way we do things around here.” Assumptions influence our focus, our oversights, our values, and our dismissals. While making decisions based on experience can be effective, the ever-changing, disruptive nature of our world necessitates a continuous reevaluation of our assumptions to ensure they still hold true.

Leaving a Trail

An interdisciplinary team from the University of Bristol uncovered fascinating behaviour within the realm of the rock ant. This species engages in a form of chemical dialogue, marking territories already scoured with a distinct pheromone trail. This “negative trail” acts as a sign to save precious energy, guiding fellow ants away from previously redundant explorations. This natural strategy of avoiding unnecessary repetition offers a compelling analogy to the world of corporate innovation.

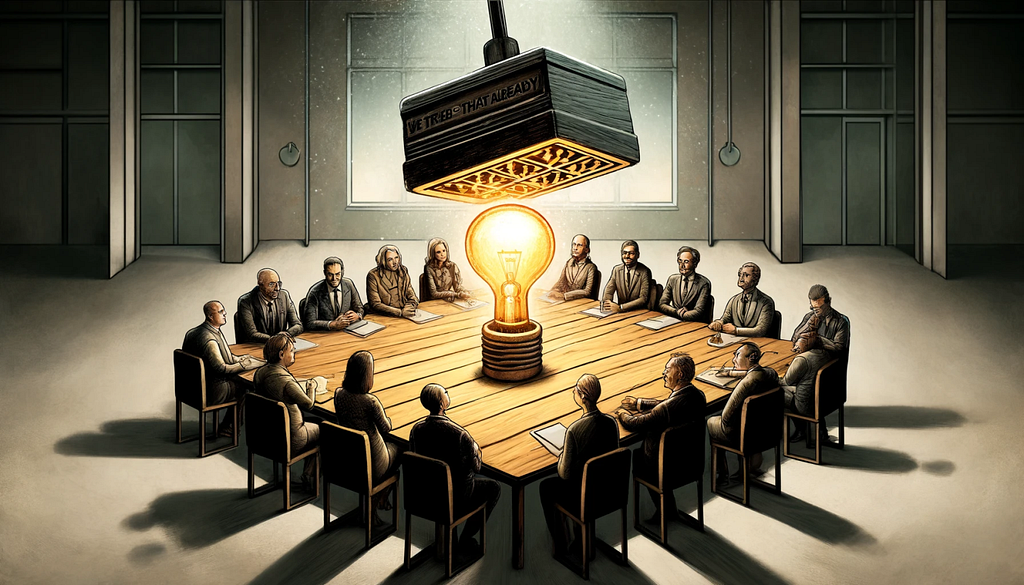

In the corridors of corporate life, like many readers, I’ve experienced firsthand how the familiar phrase “We’ve tried that already and it didn’t work” can serve as both a shield and a sword. It’s a defence mechanism wielded by those fearing change, as well as an offensive strike against the rise of new ideas. In one such organisation, senior figures staunchly maintained that an innovation-themed show — a project that eventually became The Innovation Show (now celebrating its eighth year) — was doomed to fail, having supposedly been attempted and abandoned.

This resistance can stem from various motivations. At times, it’s a well-intentioned caution, like rock ants, aimed at conserving valuable resources by not retreading unsuccessful paths. More insidiously, however, it can originate from a place of corporate jealousy, fear of being overshadowed, or sheer resistance to change. These dynamics highlight the complex, often hidden forces of resistance at play within organisations. Such forces shape the organisational journey towards transformation and innovation — or, conversely, towards stagnation and decline.

For the sake of this week’s Thursday Thought, let’s suppose “We’ve tried that already and it didn’t work” stems from well-intentioned colleagues. We share two illustrative examples of McDonald’sand Pitney Bowes. In the case of the latter, our guest on The Innovation Show, former CEO and Chairman of Pitney Bowes Inc. , Michael Critelli shared how re-examining assumptions paid dividends for the organisation.

Revisiting Assumptions

“We have a council of senior executives that convenes regularly to look at the data and ask, Is there anything new in the environment that could change our basic conclusions? We’re constantly monitoring the landscape for changing conditions.” — Michael Critelli

A noteworthy illustration of revisiting assumptions comes from Pitney Bowes’ attempts to expand into the French market. Pitney Bowes’ attempts to establish a foothold in France saw them eyeing the acquisition of a particular company, Secap, which uniquely wasn’t in competition with us in the United States, thus allowing the company to grow while avoiding regulatory hurdles from the U.S. Justice Department. In 1995, SACAP fell under the ownership of a notable private equity investor, Marc Ladreit de Lacharriere who, initially, was not open to selling. However, by 1997, de Lacharriere hinted at a possible sale for 1.5 billion French francs — approximately 300 million U.S. dollars.

Then CEO, Critelli, held annual meetings with the Secap owner and would always conclude with a consistent 100 million dollar valuation gap. However, when the European Union solidified and introduced the Euro as a common currency, Critelli saw an opportunity. This piqued de Lacharriere’s interest in reallocating his investments towards other EU-based companies, preferring transactions in Euros.

With the exchange rate moving to eight French francs to the dollar, 1.5 billion French francs now translated to just under 200 million U.S. dollars. Renewed negotiations led Critelli to agree on a 235 million U.S. dollar deal — a price reflecting the improvements de Lacharriere had made to Secap. This transaction not only marked one of Pitney Bowes’ most successful deals but also illustrated Critelli’s relentless pursuit of the opportunity, refusing to write it off as unfeasible due to past challenges or the owner’s initial stance.

This experience underlined a crucial lesson: the context for business decisions — be it through market dynamics, currency changes, or strategic shifts — can evolve significantly. This scenario underscores a broader lesson: what was once deemed unfeasible may become viable as external conditions evolve.

A similar mindset led Pitney Bowes to re-enter the cigarette tax stamping business in Asia decades after exiting it in the U.S., capitalising on the region’s need for anti-counterfeiting solutions.

These examples serve as potent reminders that in business, as in nature, environments change, and what may have failed at one time can succeed in another, challenging the notion of “We tried that already” as a barrier to innovation.

The Assumptions Trap

Assumption: “a notion widely accepted as true, despite lacking concrete evidence.”

“Making good judgements and acting wisely when one has complete data, facts and information is not leadership. It’s not even management. It’s bookkeeping. Leadership is the ability to make wise decisions and act responsibly upon them, when one has little more than a clear sense of direction, proper values, and some understanding of the forces driving change. It requires true leadership. It requires those who can go before and show the way. It requires educing the inherent integrity and virtue that lies within everyone waiting to be aroused and brought into play.” — Dee Hock

In our current series of The Innovation Show with Rita McGrath, we delve into Rita’s 1995 book, “The Entrepreneurial Mindset”. In this book, Rita introduces Discovery-Driven Planning and the necessity to map and challenge one’s assumptions. Rita explains how in a conventional business, managers generally use “patterns of the past” to inform “projections of the future”.

With new ventures, in contrast, we are exploring entirely new patterns. The process does not involve analysis of a reality that exists but the creation of a new reality. When it comes to exploring the unknown, when we rely too heavily on past patterns, we just may experience a similar fate to that of McDonald’s when entering the Chinese market.

The “McAssumption”

“In any highly uncertain venture, the proportion of assumptions you need to make relative to the knowledge you have is considerable. Managing when most of your decisions are based on assumptions is a completely different proposition from running an operation in which you know what is going on. You will find yourself making decisions about people, assets, markets, technologies, risks, revenues, and other critical project elements on the basis of assumptions. Under high lev- els of uncertainty, the data simply don’t exist. Nobody knows, and you won’t be an exception.” — Rita McGrath

McDonald’s is not a company run by dummies. Yet managers of the store in Beijing forgot to suspend their assumptions regarding the nature of a McDonald’s experience — after all, fast food is fast food, right? Fast food means fast turnover, and this premise guided the design and construction of the Beijing restaurant. It turned out, however, that for the average Chinese citizen, a McDonald’s meal was not a low-budget nosh but a big chunk of disposable income. So customers came in droves, and they lingered to enjoy what was from their perspective an exotic, perhaps even gourmet experience. Imagine the managers’ dismay when they realised that they had designed the restaurant for fast turnover and that the customers wanted none of that. McDonald’s eventually solved the problem in Beijing by expanding the size of the restaurant.

When McDonald’s learned from the McAssumption sandwich, it took a different approach in its early days in Russia. When the company entered Moscow, it used a different strategy. Here, a gate on one side of the restaurant would admit several diners waiting in line. After a predetermined amount of time had passed, a gate on the other side would open, everybody in the place was asked to leave, and the process would be repeated for the next group.

In the words of Matisse, the challenge of painting a rose lies not in the act itself, but in forgetting the roses that came before. This echoes true in the corridors of corporate innovation, where the spectres of past attempts loom large over the potential for new growth. The ‘McAssumption’ serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the pitfalls of relying too heavily on established norms when venturing into uncharted territories. Similarly, the story of Pitney Bowes reminds us of the rewards that await those willing to reassess and adapt to the evolving landscape.

Leadership, as Dee Hock suggests, is not merely about managing known quantities but navigating the unknown with a compass of integrity and a map of informed assumptions. It requires a willingness to question, to challenge, and to venture boldly where none have dared, or decided, to go before. As we move forward, let us carry the spirit of inquiry and innovation, mindful that every ‘tried and failed’ is but a stepping stone to ‘tried and triumphed.’

The future belongs to those who are willing to paint their roses, not in the colours of yesterday, but in the hues of tomorrow’s promise.

Thanks for Reading

That stellar series with Rita McGrath is now live, Parts 1 and 2 are below and Part 3 is on the way.

The Perils of “We Tried That Already” was originally published in The Thursday Thought on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.