“Computers are useless — they only give you answers.” — Picasso

“Never memorise something that you can look up.”― Albert Einstein

There is a story that tells how Albert Einstein was once travelling on a train. When the conductor approached to collect his ticket, he saw Einstein searching his pockets. Recognising who he was the conductor said it was ok, he didn’t need to see his ticket, to which Einstein responded, “Thank you, but if I don’t find my ticket I won’t know where to get off the train.”

It was claimed that Einstein had a very poor memory, in another story, it was said that he could not remember his own phone number. This idea of the absent-minded genius is prevalent, but the reality is that great minds do not waste mental bandwidth on meaningless information. Einstein was not forgetful, he chose not to waste any mental energy on information that he could simply look up.

As a young child, his parents worried that he could not speak, but when he did he started asking many questions at home and in school. His teachers told him he was disruptive to his class, that he should ask fewer questions and that he would never amount to anything unless he learned to “behave like all the other students”.

Thankfully, Albert didn’t want to be like the other students, he valued the pursuit of big questions over short-termism of small answers.

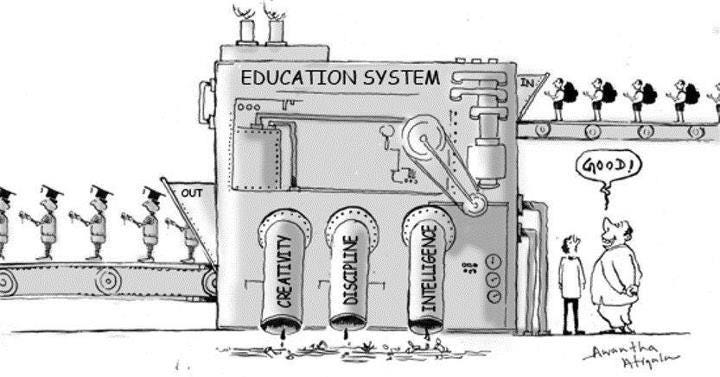

Beating Out the Curiosity?

“Kids are never the problem. They are born scientists. The problem is always the adults. They beat the curiosity out of kids. They outnumber kids. They vote. They wield resources. That’s why my public focus is primarily adults.” — Neil deGrasse Tyson

The undervalued gift of curiosity is often stamped out of children at a young age. Curious kids ask their parents an average of 73 questions a day. Shamefully, by middle school, they have all but stopped asking questions. The lesson they learn is that they are commended for knowing answers and reprimanded for asking questions.

English philosopher John Locke said too many children find “their curiosity baulked (hindered/thwarted) and their questions neglected.” However, he added that when adults attempt to answer a child’s questions, they encourage even more questions and encourage a spirit of questioning. While research suggests that curiosity naturally tends to fade, we must also recognise that children are discouraged from asking questions in the first place.

This Christmas, Santa brought our 9-year-old and 5-year-old sons an Amazon Alexa. The boys ask questions, the answers to which, my wife and I sometimes do not know the answers. This is when we commend them for their questions and tell them that questions carry great value and to keep thinking like that. They realise that they are free to question the world and they do not need to take adults “word as gospel”. This is also a sign of our times, where technology is on the verge of surpassing humanity in the realm of “rote intelligence”.

The challenge for humanity is to encourage our children to continue their questioning of a society, which does not like to be questioned. The founder of Philosophy for Children, Matthew Lipman said of children “Why do they ask so many metaphysical questions while still young, then seem to suffer a decline in their powers as they move into adolescence?”

The great broadcaster and natural historian Sir David Attenborough once met former U.S. President Barack Obama in the Oval Office. The following exchange took place, which echoes the point that we lose our curiosity and natural skill of asking questions.

Obama: “How did you get interested in nature and wanting to record it?”

Attenborough: “Well, I’ve never met a child who’s not interested in natural history. Kids love it. Kids understand the natural world and they’re fascinated by it. So the question is, how did you lose it?”

Education Must Adapt to a New World

In 1903, John D. Rockefeller founded the General Education Board in the USA. Education was focused on developing obedient, compliant citizens. The nascent enterprises of the industrial revolution needed reliable workers who would show up and do as they were told. These workers were not educated to think laterally, let alone to think critically. While the elite class of that era was funding a workforce fit for the period of time, we are still living with the frameworks and mindsets of that education system. That education ethos is no longer fit for purpose. To change that system is a huge undertaking and thankfully we are seeing signals that change is underway with smaller schools dedicated to teaching children “how to learn” and how to be adaptive to a world in flux.

Whatever about basic education, business schools do not train people to ask great questions and why should they, do businesses value these skills? Success in education is still based on retaining information for as long as is required to pass an exam and get a qualification. As soon as we get that qualification, the information is often forgotten, never to be used again.

The real value comes from connecting thoughts, merging concepts and you got it, coming up with new questions and new insights — connecting dots trumps collecting dots. True learning comes from pushing boundaries, the scar tissue of failure and the courage to ask meaningful questions in the first place.

There is a saying “If you are the smartest person in the room, you’re in the wrong room.” This concept not only suggests that you should hire people smarter than you, but you should also have the ability to ask great questions of those people. However, organisations are often looking for workers who will just “do” and not question “why they do what they do”. In addition, we are more comfortable coming up with fast solutions rather than uncovering if we are solving the right problem. Another Einstein quote sums this up: “If I had an hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” This is great in theory, but do organisations value this? In most boardrooms, executives are valued for their suggested solutions more than their defined problems.

We can be forgiven for thinking that the job of education is to give us answers. However, I truly believe the job of education is to give us the tools to ask profound questions and the courage to seek our own answers.

Knowing how to read and write are the foundations of critical thinking. Critical thinking leads to new information, novel insights and eventually disruptive questions. A combination of imagination, courage and unwavering belief in one’s ideas is how our world progresses. As founder and CEO Emeritus of Visa, Dee Hock says: “Few adults of great achievement were cooperative, conformist children, or students. They were more often shunned iconoclasts protecting themselves as best they could from the contempt and persecution of less adventurous adults and children”.

For me, Picasso said it best “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up”.

I would like to add that we are all natural explorers, it is the very essence of humanity. Some of us may choose to become tour guides, but that choice should be our own. We should not be ushered towards this decision by society, by parental (over)guidance or by education.

I leave you with some fundamental questions inspired by the poem below by Lebanese-American writer, poet and visual artist, Khalil Gibran.

Do we encourage our children to ask questions?

Do we encourage our people to ask questions?

Do we even ask questions of ourselves?

“Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love but not your thoughts,

For they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow,

which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

You may strive to be like them,

but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children

as living arrows are sent forth.

The archer sees the mark upon the path of the infinite,

and He bends you with His might

that His arrows may go swift and far.

Let your bending in the archer’s hand be for gladness;

For even as He loves the arrow that flies,

so He loves also the bow that is stable.” — Khalil Gibran

The latest episodes of The Innovation Show touch on some of the points raised above.

Episode 141 is “Parallel Mind, The Art of Creativity” with Aliyah Marr

Aliyah uses practical examples and guides us through conceptual, transpersonal art experiments to demonstrate how we can use the power of art to access our inner child, express our buried emotions, and use any form of art as a catalyst to transform our lives.

Pure creativity is an activity that has no predefined destination or purpose, while applied creativity is an activity that always has a goal or application in mind. Pure creativity can be seen as a kind of play, while applied creativity is usually seen as work.

We talk:

Creativity

Left and Right Brain

Open Focus

The Inner Child

The benefit of Limitation

Limiting Beliefs

Internal Dialogues

Overcoming Fear

Have a listen:

Soundcloud https://lnkd.in/gBbTTuF

Spotify http://spoti.fi/2rXnAF4

iTunes https://apple.co/2gFvFbO

More about Aliyah here: