“You can’t allow tradition to get in the way of innovation. There’s a need to respect the past, but it’s a mistake to revere your past.” — Bob Iger

Throughout history, women did the gathering and men did the hunting. Women tended to provide the staples, whether roots, seeds or shellfish. The staples required processing, which involved a lot of time, it was laborious, unseen, under-appreciated work. The women worked hard at such tasks because their children and husbands relied on the staples women prepared. Men, by contrast, searched for foods that were especially appreciated, but could not be found easily or predictably. They hunted for such prizes as meat and honey. A successful hunt brought huge happiness to the camp and everyone celebrated the victory. (We explore this further with Richard Wrangham on this week’s innovation show.)

The point I wish to make with this analogy is that corporate innovation workers tend to overlook the hard work of those in the core business. Innovators focus on the new, new product, new business model, or new disruption. When we do this, we forget that it is the core business that financially supports such exploratory work. Without the core providing “the staples”, we would not have the opportunity to “bring home the bacon” in the form of an innovation. When we include the core business as an equal partner in exploration, the relationship can evolve in unison and the old can integrate with the new and a new entity will evolve.

Closer to home, my wife maintains our household. It is always immaculately clean and tidy. She keeps the dishwasher empty and the kitchen counters clean. She keeps the refrigerator stocked up and the clothes clean. When I get to do a project such as painting the fence or planting a tree, I always accept it gratefully, rarely do we get to do these manual jobs. People always notice and praise such work, because it includes a shiny new thing. Something new that was not visible before. And therein lies the problem.

In contrast to the essential, consistent job my wife does to keep the household flowing, people don’t notice that. They only notice the new shiny thing. This means the person responsible for keeping the ship afloat, which affords you the time to paint the fence gets no credit, no recognition, no praise. You will agree that it must feel pretty bad. That feeling is precisely what the core business feels like when the innovation team gets praise for making a breakthrough. The core business feels like they are the ones who afford the innovation team the time to experiment and time to fail just so they can succeed. Unfortunately, we overlook these contributors, those who provide the staples and instead all attention goes to the new shiny thing. This is where we can learn the lessons of Janus.

Janus Innovation

“We must welcome the future, remembering that soon it will be the past; and we must respect the past, remembering that it was once all that was humanly possible.” — George Santayana (Spanish philosopher, essayist, poet, and novelist)

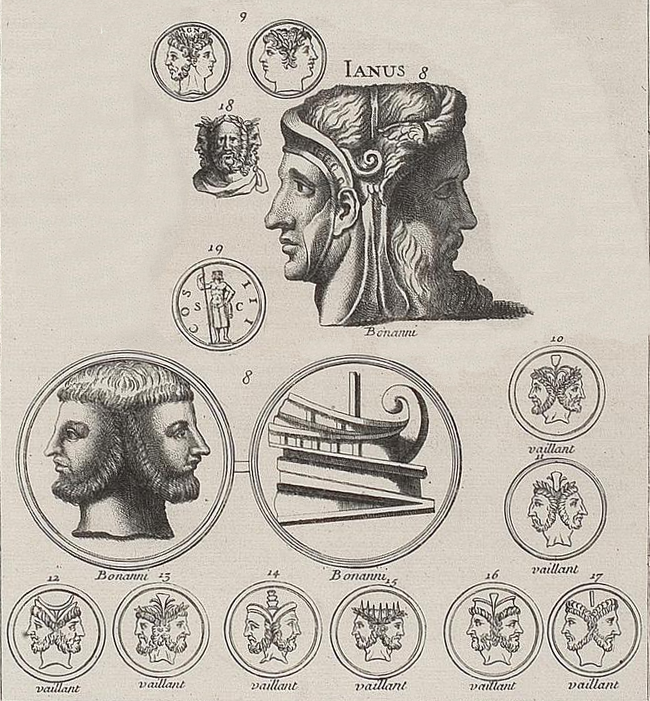

In ancient Rome, Janus was the god of beginnings, births, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, and endings. Janus is depicted as having two faces, one face looks to the future and one face looks to the past. For today’s Thursday Thought I would like to propose we consider the symbol of Janus to frame corporate innovation work within established organisations.

In many established corporations, rifts exist between the innovation team (perhaps even the digital team) and the legacy organisation workers. The reasons are many, but a main reason for the rift is that the people who got the business where it is today and still maintain that business amidst a turbulent business world feel that the organisation is squandering hard-earned profits on shiny new things, most of which fail. As a changemaker, we must be empathetic and see innovation exploration from their perspective. Why? By seeing it from their side, we can understand the shortfalls in communication. The communication of what innovation is and what it aims to achieve is essential. This is not only a must have to ensure harmony between the old and the new, but it is doubly important for the innovation team themselves. They must understand what they represent to the organisation as a whole, but also so they are clear on the fuzzy target they are aiming for. If you have no target, no matter how vague it is, you will never reach it.

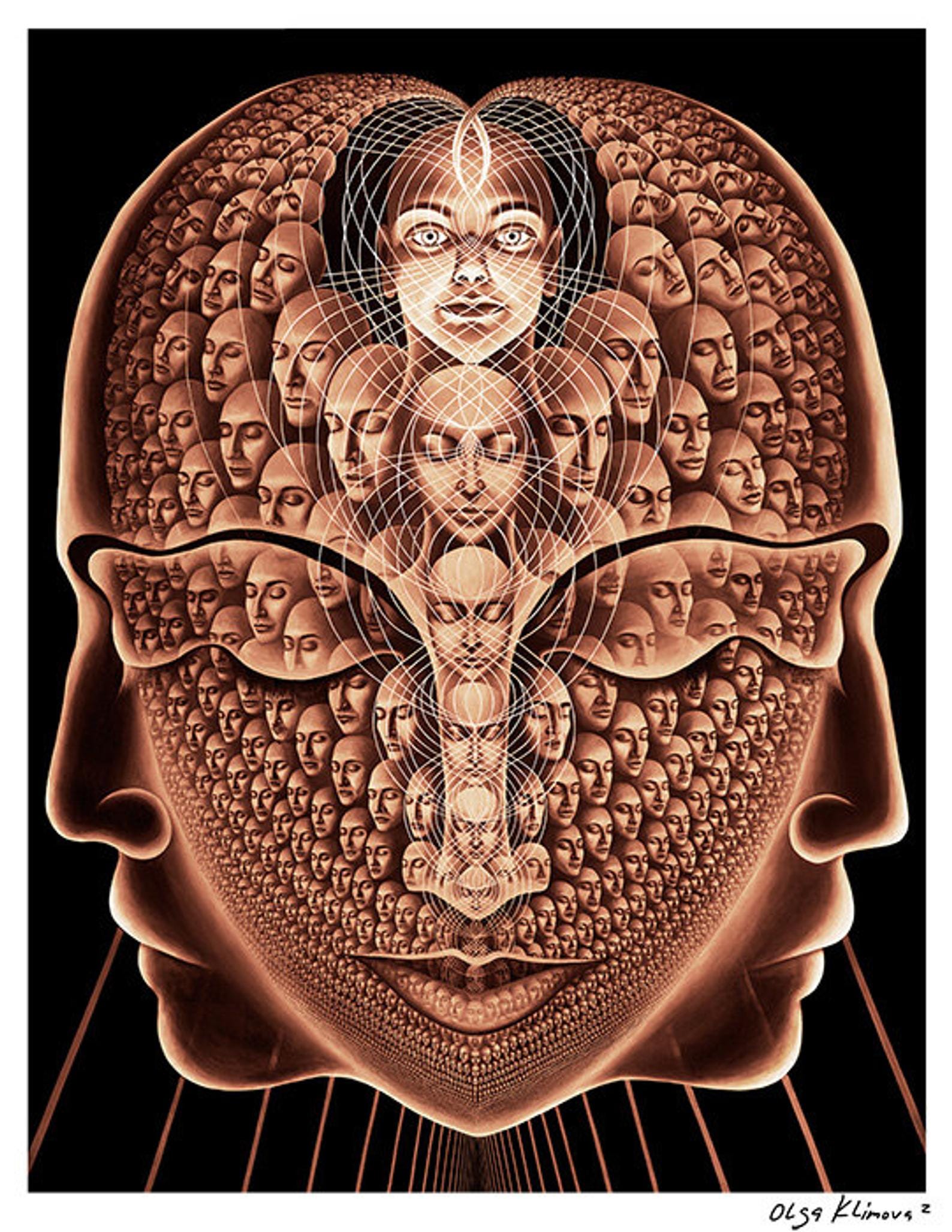

“Janus Innovation” represents a fruitful partnership between the business as it was, as it is and as it shall be (represented by the image above, faces looking every direction). Janus Innovation is a mindset that incorporates the past to build the future. Janus Innovation ensures that credit is given to those who provide the staples, which funds the innovation team to hunt the future.

Thanks for Reading

Episode 191 is “Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human”, with Richard Wrangham

Our guest argues that it was cooking that caused the extraordinary transformation of our ancestors from apelike beings to Homo Erectus.

At the heart of this episode lies an explosive new idea: the habit of eating cooked rather than raw food permitted the digestive tract to shrink and the human brain to grow, helped structure human society, and created the male-female division of labour. As our ancestors adapted to using fire, humans emerged as “the cooking apes”.

Covering everything from food-labelling to sexual division of labour to raw-food faddists, Catching Fire offers a startlingly original argument about how we came to be the social, intelligent, and sexual species we are today.

A fundamental question that every culture answers in a different way, but only science can truly decide and one today’s guest deeply explore is What made us human?

Our guest’s work proposes a new answer. He is a true changemaker, driven by curiosity and believes the transformative moment that gave rise to the genus Homo, one of the great transitions in the history of life, stemmed from the control of fire and the advent of cooked meals.

Fire was our first technology. Cooking increased the value of our food. It changed our bodies, our brains, our use of time, and our social lives. It made us into consumers of external energy and thereby created an organism with a new relationship to nature, dependent on fuel.

Have a listen:

Soundcloud https://lnkd.in/gBbTTuF

Spotify http://spoti.fi/2rXnAF4

iTunes https://apple.co/2gFvFbO

Tunein http://bit.ly/2rRwDad

iHeart http://bit.ly/2E4fhfl