“To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” — Twain/Maslow/Kaplan/Baruch/Buddha/Unknown

The Law of the Instrument

The law of the instrument, otherwise known as Maslow’s hammer is a cognitive bias that involves an over-reliance on a familiar tool. As Abraham Maslow said in 1966, “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

A hammer is not the most appropriate tool for every purpose. Yet a person with only a hammer is likely to try and fix everything using their hammer. often without even considering other options. We prefer to make do with what we have rather than looking for a better alternatives.

This Thursday Thought explores how the law of instrument is prevalent in change management, disruption, innovation organisational transformation and digital transformation.

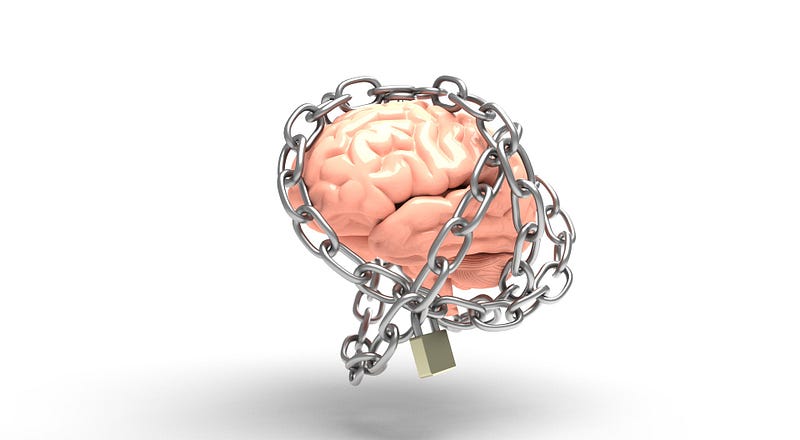

It examines the biases that lock our thinking. It also looks at why most digital transformations fail.

True transformation of any kind must be done through an integration of the right tools and the right mindset. However, we will never change business models, without first changing mental models.

The Einstellung Effect

Einstellung is the development of a mechanised state of mind. The Einstellung effect is the negative effect of our previous experiences when solving new problems.

Einstellung refers to our predisposition to solve a given problem in a specific manner even though better or more appropriate methods of solving the problem exist. (Maslow’s Hammer)

In 1942 renowned psychologist Abraham Luchins conducted an experiment to illustrate the Einstellung effect. Luchins gave subjects 3 water jars with the capacity of (A) 21 units, (B)127 units and (C) 3 units, he then asked them to measure out exactly 100 units.

As you would figure, the solution is to fill jar (B)127 units, then pour out enough to fill jar (A) 21 units and jar (C) 3 units twice (to get 6 units) .

The formula would look like this: 100 units = B-(A+2C) or 127-(21+2×3).

This is where it gets interesting…

Luchins then gave the same subjects 3 new water jars with the capacity of (A) 18 units, (B) 48 units and (C) 4 units, he then asked them to measure out exactly 22 units as quickly as possible.

If you have time try it, if not, please continue for the solution.

How do people fare? Most subjects look for a similar solution to the first problem, so B-(A+2C), when the answer is much simpler. By ignoring jar (B) 48 units, we can simply add jar (A) 18 units to jar (C) 4 units and we will get 22 units or simply A+C.

When Luchins posed the same problem to a new group of subjects who were never exposed to the first test, they all chose the jar (A) +(C) solution immediately.

This test illustrates that we attempt to use the same tools to solve new problems. This pattern is not just mental, it is also physiological.

Cells that Fire Together Wire Together

No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it — Albert Einstein

In his 1949 book ‘Organization of Behavior’, the psychologist Donald O. Hebb proposes that each time a group of neurons fires together and makes a pattern, those neurons tend to fire in the same pattern again. This pattern becomes a physiological one. Hebb proposes that learning modifies the cellular structure of the brain.

This would suggest that when we learn something, the pattern of that learning is much like the groove in a vinyl record. Thankfully for us this is not the case and we can exist in a state of constant learning, which is essential for our futures.

Neuroplasticity describes the ongoing change to the brain throughout our lives. Plasticity suggests that the brain is malleable (changeable) and not limited to a fixed growth period during childhood, youth or brain damage. Neuroplasticity occurs when our brains change when something new is learned, experienced and memorised.

For a long time, we believed that as we aged the connections in the brain became fixed. Research has shown that in fact the brain never stops changing through learning, experiencing new things and connecting various ideas. Plasticity is the capacity of the brain to change with learning, mainly at the level of the connections between neurons. New connections can form and the internal structure of the existing synapses can change.

So the pathways forged as described by Hebb, can be overwritten, but this needs to be done purposefully.

Resting on our Mental Laurels

Our brains are constantly seeking ways to conserve energy. We are still not too far evolved from the days where our main concern was to stay alive when we had to run from man-eating predators. The brain still holds on to this heritage. In order to ensure survival and conserve energy to survive, most things habitual are stored in the basal ganglia.

Routine shortcuts include punching in your phone password or setting the alarm at night or simply locking your door. You know when someone asks you “Did you put the alarm on?” and you sometimes can’t remember, but when you check you inevitably did so? This is a primed embedded habit. This is your brain at work saving you precious energy.

Almost 50% of what we do every day is driven by habit, many things we do, we do on autopilot.

As we saw earlier the Einstellung effect is one of the ways our brains find a solution as efficiently as possible, even though it might not be the most appropriate solution.

In a study called “The Neuroscience of Leadership” Dr David Rock and Dr Jeffrey Schwartz tell us that even when we enjoy new experiences, create new connections and digest new information eventually we will ignore these after a while, once we become habituated to new stimuli.

It has been proven that new experiences in relationships for example, such as new restaurants, concerts etc. lead to releases of dopamine and endorphins and thus keep the relationship feeling fresh and exciting.

Once habituated to anything in life it becomes difficult for us to change. The more entrenched our habits or neural circuits become, the more our minds resist new ideas.

We experience this as we age and we follow a set mental routine. Our brains treat new ideas or experiences as threats and trigger our amygdala, the fear centre of our brains (the amygdala is the reason we are afraid of things outside our control).

“The human mind treats a new idea the way the body treats a strange protein, it rejects it.” — P.D. Medawar (Biologist)

Why Digital Transformations Fail

“To change the government, you must change the minds of the governed.” — Ross Ulbrich (Founder of The Silk Road)

There are two essential “forces” in every organisation.

There are the mechanical forces, business models, processes, strategies, regulations, policies and procedures.

Then there are human forces, the people who make the mechanical forces happen.

When these forces are out of sync problems arise.

According to Forbes, 7 out of 8 digital transformations fail.

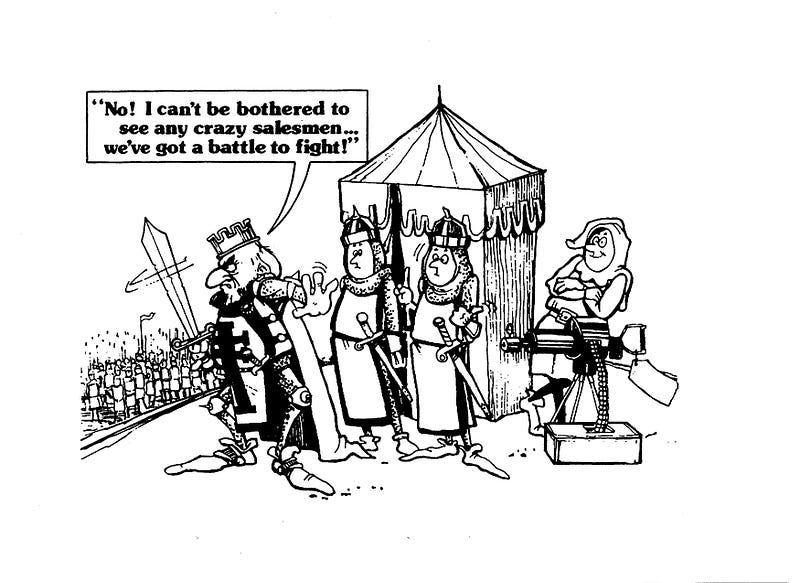

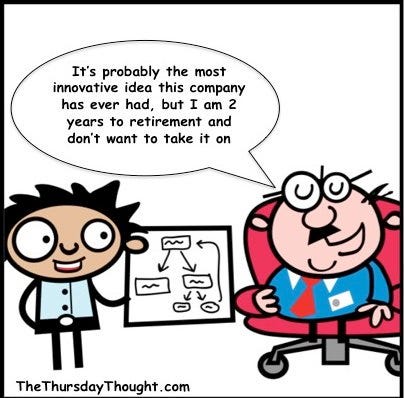

Despite our best intentions. we tend to apply what we know best (we use a hammer) to situations that require new thinking (when we may need a new tool). When most companies initiate transformation initiatives, they begin with new policies, new procedures, new strategies. They begin with the mechanical side of business. We hope this will mean we don’t need to deal with the much harder transformation, which is the people part.

This is why according to this recent survey by Fujitsu, global scale digital change initiatives failures cost on average €555,000. We try to paper over the (human) cracks and hope digitisation of old models might be enough to start the snowball effect of change. This may come in the guise of a new website, the use of a new collaboration tool or even a 1 or 2 day strategy retreat. The latter is akin to going to the gym once per month and expecting results.

We forget it is the people who make strategies stick. We cannot change business models without first changing mental models.

Digital business models require different measurement than their predecessors, so to make them work we need new metrics. New metrics mean new reward and recognition structures.

Think about trying to make structural changes to an old house, sometimes you might be better building a brand new house, sometimes you may need a new foundation. You can not hack on a new piece and pretend it will all work out fine, although this happens all the time.

While some efforts are truly legitimate and fail due to our unconscious bias to use old solutions to solve new problems, many other initiatives fail because they are not fully embedded by senior leadership.

They are but lipstick on a pig and the organisation is often just rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic and often are blocked by transient power brokers for a variety of reasons.

Unlearn, Relearn

Founder of the Silk Road, Ross Ulbricht said “To change the government, you must change the minds of the governed.”

To change what people do, we must first change how people think. To change how people think we often need to teach people to unlearn before they relearn. If people are unwilling to unlearn and relearn we need new people.

The way society is structured we learn in school to get a college place. We learn in college to get a job place. We learn in the workplace how to keep our place. However, we often stop learning.

Most people get trained to do one job and their learning stops. It is partly the responsibility of the organisation to facilitate continuous learning, but it is wholly the responsibility of the individual to make learning a priority.

UCLA’s Bhagwan Chowdhry says “The distinction between work and learning might need to become more amorphous. We currently have a dichotomy where those who work need not learn, and those who learn do not work. We need to think about getting away from the traditional five day working week to one where I spend 60% of my time doing my job and 40% learning on a regular basis.”

In a business environment of mass disruption and exponential change, we must learn how to unlearn and relearn. We must learn how to think critically. We are often prisoners of our unique growth experiences and the inescapable biases that surround us. The strategic thinker of tomorrow is she who challenges her own thinking, questions everything, engages all the senses and makes holistic decisions.

Alvin Toffler put it best in his 1970 classic book “Future Shock”

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.” — Alvin Toffler

On this week’s innovation show, we are treated to a variety of exercises to challenge and expand our thinking.

EP 103: How to Think Like Leonardo Da Vinci — Michael J Gelb

We live in a world of unprecedented disruption. But we are all born of the sun, and travelling towards it. We are joined by Michael J. Gelb, a specialist in innovation and creativity, founder of The High Performance Learning Center and author of ‘How to Think Like Leonardo Da Vinci’.

How to Think like Leonardo da Vinci is a guidebook, inspired by one of history’s great souls, for that journey. This book is an invitation to breathe the vivid air, to feel the fire in your heart’s centre, and the full flowering of your spirit.

We talk about the seven DaVinci principles and some exercises to hone these skills and how we might introduce them for a more satisfying life.

Have a listen Web http://bit.ly/2FwsOJw

Soundcloud https://lnkd.in/gBbTTuF

Spotify http://spoti.fi/2rXnAF4

iTunes https://apple.co/2gFvFbO

Tunein http://bit.ly/2rRwDad

iHeart Radio http://bit.ly/2E4fhfl

You can find out more about Michael J. Gelb here: https://michaelgelb.com/