“The New always looks so small, so puny, so unpromising next to the size and performance of maturity.”

– Peter Drucker

Imagine you have a 500k mortgage and a modest car earning 120k per year. You don’t have much left in your account monthly after household expenses and your kids’ college tuition fees. When you see people driving a luxury car, you scoff, “what a waste of money”. As luck would have it, you win the lottery. Overnight, you have $40m in your bank. From the perspective of your current resources, a luxury car no longer appears to be a waste of money. While you’re at it, as well as the car, you buy a multi-million dollar crib too. The cost of the car and the house is relative to how much you have at your disposal.

Thanks for reading The Innovation Show! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

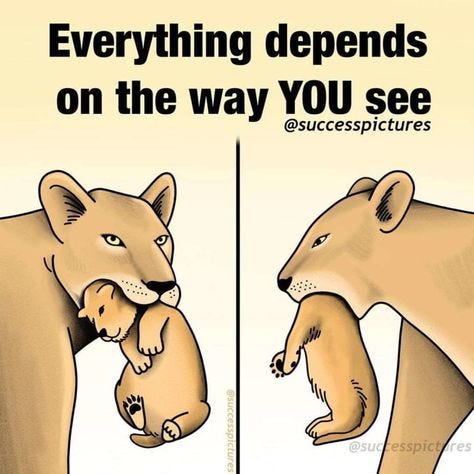

Everything is relative.

Clayton Christensen described this same relativity problem in the context of organisational resource allocation. “An opportunity attractive to a firm that has $50 million in sales and seeks 10% top-line growth would be unattractive to a firm with $5 billion in sales and seeks 10% top-line growth. A $2.5 million opportunity meets 50% of the first firm’s growth needs but only 0.5% of the second firm’s growth needs.” Which company will prioritise going after a $2.5 million market?

Everything is relative.

The same innovation has very different implications for different companies.

One Firm’s Junk is Another Firm’s Gold

“Low-end disruptors find success when they stealthily take advantage of asymmetries of motivation by targeting customers whom existing competitors are happy to shed.”

– Clayton Christensen, Scott D. Anthony, “Seeing What’s Next”

A firm’s resources, processes, and values filter the way a firm looks at a budding innovation. Firms with different resources, processes, and values can look at the same innovation and see very different things. For instance, some firms looked at the Internet and saw a nifty way to lower internal costs. Other firms looked at the Internet and saw a vehicle capable of driving new growth. In the language of Clay Christensen and Roy Adner, this is an example of asymmetric motivation. A meaningful growth opportunity for an incumbent will differ significantly from a start-up’s. In many cases, the incumbent held all the chips to make informed bets on its future, but asymmetric motivation gaffed the dice.

History is replete with examples where bankrupt organisations had all the ingredients they needed to endure, but their perspective biased their evaluation. In many cases, engineers at established firms had invented the same technology that led to their firm’s demise. However, the entrants led the commercialisation of disruptive technologies rather than incumbents because of the relativity problem.

Steve Sasson, a young engineer, prototyped the first digital camera from within Kodak, but Kodak chose to shelve the opportunity. Similarly, Polaroid was a leader in developing digital imaging technology far superior to its competitors. In Nokia, engineers presented a touchscreen phone years before Apple rolled out the iPhone. In all these cases, the same leaders responsible for the organisation’s success in one perspective made decisions that led to its demise in another.

The initial absolute size of a disruptive opportunity is generally too small to justify any substantial investment or even management attention. Disruptive opportunities are considered a distraction through the lens of maturity and success. It is not that leaders don’t see the disruption coming; they choose instead to double down on what they know and do best.

Even when firms don’t develop the disruptive in-house, they sometimes pass on the opportunity to license or acquire the fledgeling opportunity. In our forthcoming series with Michael Tushman, Charles O’Reilly and Andrew Binns, we consider what happened with the emergence of the quartz watch (See the books: “Winning Through Innovation” and “Lead and Disrupt”.)

For over a century until 1960, the Swiss dominated the watch industry. In the 1860s, the Swiss made cheaper clocks and displaced the British as the world leader. In the mid-1960s, Omega, a great watchmaker founded in 1848, provided a research grant to two engineering faculty members at the University of Neuchatel to explore the idea of an electronic watch.

In 1968, they presented their findings to the company’s senior managers. The researchers had discovered and patented elements of the basic technology to make an electronic watch and offered it to Omega, their benefactors. What was the reaction of Omega senior management? They turned the offer down. The new approach to making more accurate and cheaper timepieces threatened their core identity as a maker of high-quality watches, obviated their deep skills in precision mechanical engineering, potentially threatened their brand, and would require them to sell to a different customer segment of more price-conscious consumers. It was also a low-margin business.

Do you think this sounds familiar to you? What happens in such cases? Several months later, Hattori-Seiko, a little-known Japanese company, licensed the technology.

The Swiss watch industry dominated for a century. It was destroyed in only 15 years: 800 companies went out of business, and 50,000 people lost their jobs. It was only when SSIH/ASUAG (the Swiss watchmaking consortium) went bankrupt and a new CEO, Nicolas Hayek, was brought in that the Swiss embraced the new technology. Under his guidance, Swiss companies began making both electronic and mechanical watches. They ultimately emerged once again as the world leaders based on revenues, competing at the low end with Swatch and Flik Flak, the medium range offering it to Omega.

Stemming the Bleed

This perspective problem is even worse when an incumbent is in freefall. I led digital transformation and revenue generation in a media company. When our small team generated revenue, we celebrated small wins. Those digital dimes were small compared to analogue dollars, but to us, they proved we could generate new revenue with fewer resources and higher profits. However, because the industry was in free fall, those small wins were barely even recognised by leadership. They appeared insignificant compared to the losses. The company needs a big revenue win to balance the losses. The company may make a few Hail Mary passes, but they rarely go to hand.

This is why we believe it is often easier to build from zero. In these cases, we have no legacy systems, mental models and business models to contend with. We have no status quo bias, ego, or fear of irrelevance to overcome. This is why many people believe that the only way to deal with change management is to change the management.

For a quick diagnosis of your organisation, you can undertake two quick tests:

The first is to look at your income statement. What is its revenue mix? Does it earn a significant proportion of its revenue from various products or a specific subset of products? From postsales service? A company is always unlikely to prioritize opportunities that cannibalise significant revenue streams.

The second is to look at the calendar of your leaders and managers. Do they devote the majority of their time to existing operations? Do they apportion any time to explore the future?

To learn more, you can check out our Clayton Christensen tribute series, but also stay tuned for our upcoming series with Tushman, O’Reilly and Binns. These theories, taken together, provide a robust understanding of successful and unsuccessful innovation efforts.

Thanks for Reading